Stemming diabetes

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 09 :: Oct 2024

Stem cell therapy enables patient to produce her own insulin, replacing jabs, marking a breakthrough in treatment.

Scientists in China have developed a stem cell therapy for type 1 diabetes (T1D) and confirmed its efficacy by making a patient produce her own insulin less than three months after receiving a transplant of reprogrammed stem cells. The clinical findings were reported in Cell (bit.ly/Insulin-Stem).

The patient, a 25-year-old woman from Tianjin in China, has suffered from T1D for nearly 11 years and has been taking daily insulin jabs. The scientists, who followed up on the patient's condition for a year after the transplant, say she has achieved insulin independence and her glycated haemoglobin, an indicator of long-term systemic glucose levels, remained around 5%, which is similar to that of a non-diabetic person. More importantly, her blood glucose levels remained in the target range (70-180 mg/dL) for over 98% of the day. Two more volunteers have undergone the procedure, but their data are still to be analysed as they are yet to complete one year since the transplant.

"We are very encouraged by the positive clinical findings seen in this first patient," says Hongkui Deng, a cell biologist at Peking University in China, and a lead author of the study. "...these findings set a strong foundation for stem cell-derived islet transplantation as a treatment modality for diabetes that has the potential to benefit many T1D patients."

"We are very encouraged by the positive clinical findings seen in this first (type 1 diabetes) patient."

– Hongkui Deng

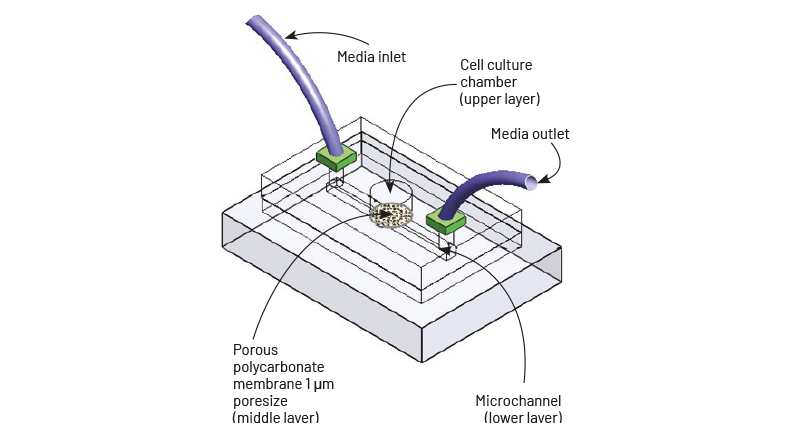

Deng and his colleagues extracted cells from the three T1D patients and reverted them into a pluripotent state, a state of immature stem cells that give rise to diverse cell types, so that they can be moulded into islets – insulin-producing cells – using chemicals. These cells are known as chemically induced pluripotent stem cells. "Employing small molecules as reprogramming factors provides a greater degree of control – small molecules have defined structures that are easily manufactured and standardised, are not genome-integrating, and are cost-effective," says Deng.

The scientists transplanted the islets not into the liver, as is the normal practice, but in abdominal muscles. Monitoring the cells in the liver is next to impossible, but in the abdomen, they can be observed using MRI and even removed, if needed, says Deng.

But, T1D being an autoimmune condition, these transplanted cells are considered by the immune system, despite being one's own, as "foreign" and, thus, attacked. The patients may have to take immunosuppressants with the therapy. The scientists could not test this in the first patient because she was receiving immunosuppressants already for a previous liver transplant.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH