What Neanderthals' teeth say about them

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 05 :: Jun 2024

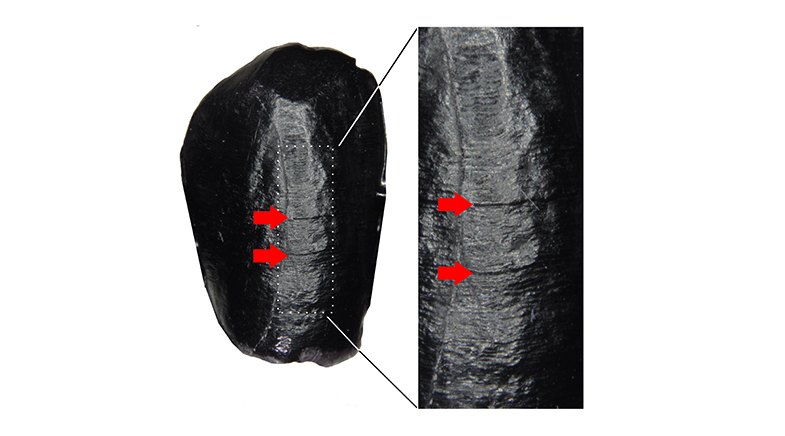

Ancient teeth provide a window into our evolutionary past.

Neanderthals, a group of extinct humans who lived from 400,000 to 40,000 years ago, are thought to have faced more stressors in life than early modern humans. A study based on the largest sample of dental archaeological remains now suggests that the two groups faced similar levels of physiological stress – say from illness or nutritional deficiency – during development. But the stress peaked at different growth stages.

Teeth are very good proxies for dietary questions in anthropology and archaeology, says Laura Sophia Limmer, a graduate student at the University of Tübingen, Germany, and first author of the study published in Scientific Reports (go.nature.com/4bwVu4H). "They really preserve well due to enamel being such a hard tissue."

Limmer and colleagues examined over 850 ancient teeth samples, about half of which belonged to Neanderthals and the rest to modern humans of the Upper Palaeolithic era (50,000 to 12,000 years ago). The samples are so precious that the researchers made high-resolution, epoxy replicas of them before analysing dental defects, such as pitting and grooves.

Because teeth are formed during childhood and don't remodel, "you always keep this childhood record", says Limmer. Enamel, which deposits periodically during development, retains signs of stressful events as there is a sudden stop or disruption to its formation, Limmer elaborates. "We analysed it throughout the dental development, and established like a very early childhood phase, then a phase of weaning and then this post-weaning phase." That's where the researchers found subtle differences between Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens.

Teeth are very good proxies for dietary questions in anthropology and archaeology.

In the early modern humans, stress-induced defects of the enamel peaked during weaning i.e. the period of transition from breastmilk to solid foods. But in Neanderthals, the researchers found the post-weaning phase (late childhood) to be the most stressful. "Neanderthal children had to be independent earlier, maybe to adapt to adult-like behaviour of collecting their own food, at least part-time, where they were more susceptible to nutritional deficiencies," says Limmer.

"Somehow Upper Palaeolithic modern humans managed to reduce this post-weaning stress in their children," adds Limmer. It could be a social strategy or behaviour such as living in bigger groups with more people contributing to the provisioning of a child that gave modern humans the advantage.

"This is a really interesting paper that attempts to get to grips with an important question in human evolution, which is whether Neanderthals and our anatomically modern version of Homo sapiens experienced the same or different pressures on growth or development," says Brenna Hassett of the University of Central Lancashire, U.K.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH