No stone unturned

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 09 :: Oct 2025

Archaeologists are piecing together the story of the hominin occupation in South Asia, envisaging the lives of the people.

On a cloudy August afternoon, a group of history lecturers sat in a semicircle on tree stumps, handling chunks of old rock, each the size of a melon. They were participants at a workshop, replicating techniques used in the Old Stone Age to make tools for survival. The cores, or mother pieces, were large and dark chunks of quartzite or quartzite sandstone, rocks used by the ancient relatives of modern humans who lived over a million years ago. Those ancestors held and manipulated such rocks to make tools.

Understanding tool-making is a crucial part of prehistoric archaeology. Tools help draw a broad picture of the age.

Kumar Akhilesh, an archaeologist and co-founder of the Chennai-based Sharma Centre for Heritage Education, showed the group of historians how to deliver a slanting hit on the rock with a smaller stone. After a few attempts, the participants at the workshop convened by the centre successfully cleaved the core rock to get smaller and thinner leaf-like flakes. Kumar Akhilesh then proceeded to show them how, by gently tapping along the outer edges of the leaf-shaped flake, they could develop serrated edges, transforming the flake into a tool which could be used to scrape and process food. And the teachers learnt the million-year-old technique of making a biface or a scraper.

This process, a simple example of ancient technology, is one of Kumar Akhilesh's areas of expertise, for which he was trained in India and France. He is a rare scholar among archaeologists, having specialised in the study of tool-making and analysis.

Understanding tool-making is a crucial aspect of prehistoric archaeology. In India's humid, tropical climate and acidic soil sediments, bones, grains, and other such biological matter degrade and vanish over hundreds of thousands of years. Archaeologists in other parts of the world, such as Africa and Europe, may find bones and other organic matter, which they use to piece together stories of human evolution and migration that date back over a million years. However, in the Indian context, stone tools are the best clues to the period; bones, when found, are a bonus. With stones, archaeologists in India envisage the lives of the people of that age. "It is like squeezing blood from stone," says Shanti Pappu, co-founder of the Sharma Centre. The institute, established in 1999, conducts research in Indian heritage, and runs public awareness and science communication programmes. With a PhD in archaeology from Deccan College, Pune, Pappu now leads her own research team.

Pappu and Kumar Akhilesh are currently excavating a site at Sendrayanpalayam in northern Tamil Nadu, which they selected out of the many sites that emerged from a study they had conducted over several years and published in 2010. Their discovery of stone artefacts, still in the process of being dated, may add a significant piece in the jigsaw of human development in South Asia. And the reasons for this expectation go back to their major discoveries in 2011, when they published the most significant discovery of the Acheulian tool dates, and 2018.

Pappu's team of researchers, including archaeologists, geologists, sedimentologists, palaeo-botanists and physicists, has, on more than one occasion, pieced together the Indian story of human evolution and migration, sometimes with startling effects. In a paper published in Science in 2011, her team wrote about its findings from trenches at Attirampakkam, in the north-west of Chennai, near a tributary of the Kortallaiyar River (bit.ly/Acheulian-Hominins). In 1863, British geologist and archaeologist Robert Bruce Foote found stone tools used by prehistoric humans in this northern Tamil Nadu site. Other archaeologists subsequently explored the site.

The paper showed the presence of stone tools that were in use 1.5 million years ago, some even earlier. It was an important discovery, for it demonstrated the presence of humans in the region earlier than previously believed.

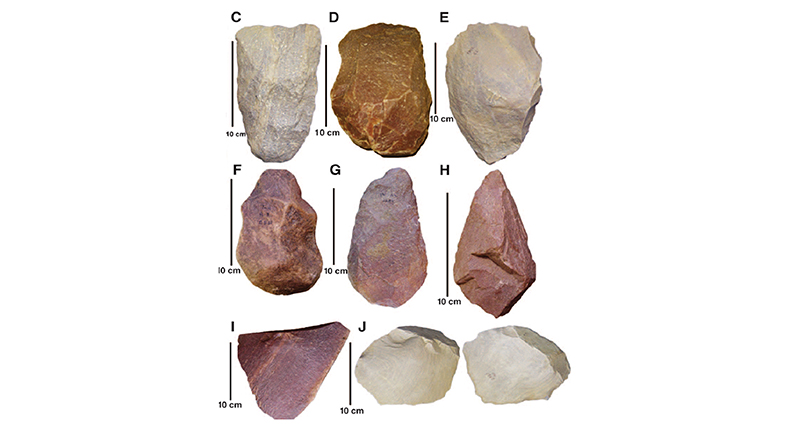

Pappu's team discovered the tools in a sedimentary layer in the trench, some nine metres below the surface. It found hundreds of tools in that deposit. Archaeologists refer to the time of the first appearance of tools such as hand axes and cleavers as Acheulean or Acheulian. Before Pappu's work, it was believed that the Acheulean 'culture' in the South Asian region emerged 600,000 years ago.

"We were very excited, and puzzled too, and called in experts to initiate a dating programme," says Pappu. Their hunch paid off. The youngest of the over 3,500 artefacts they had found was 1.07 million years old. The average age of the artefacts was about 1.5 million years.

PICTURE OF AN AGE

The tools enabled archaeologists to draw a broader picture. The Levant region (East Mediterranean) has yielded stone tools that are 1.4 million years old. The Gesher Benot Ya'aqov site in Israel has produced stone tools similar to those found in Africa, which date back to 0.78 million years. The archaeologists had earlier deduced that, starting from Africa, the Acheulean culture had made its way into the Levant and then to South Asia several hundred thousand years later. This was also considered to coincide in time with the first appearance of the Acheulean era in Europe, 0.5-0.6 million years ago. Some archaeologists believed that Homo heidelbergensis, a hominin species whose fossil was first found in Europe, brought this technology from Africa to South Asia and Europe. The theory was described in a comment on Pappu's paper in Science by Robin Dennell, now Emeritus Professor at the University of Exeter, U.K., and an expert in prehistory, especially the early human expansions out of Africa, with extensive work on China, Pakistan and Mongolia.

The materials discarded when a tool is made — powdery residue, chips of rock, leftover cores — throw light on the practices of the times.

According to Dennell, the work by Pappu and her team overturns this picture. The appearance of the South Asian Acheulean — as evidenced by the stone tools found and dated at Attirampakkam — predates the first appearance of Homo heidelbergensis. This implies that the Acheulean stone tools first found their way into the hands of Homo erectus, an earlier hominin species, which seems to have walked long distances, from the Levant into South Asia, soon after the technology emerged in Africa. It appears that several millennia later, in a second wave, this technology was taken by Homo heidelbergensis into Europe.

"The research of Pappu and her team has made an enormous contribution to the study of the earliest prehistory of India. The research at Attirampakkam showed the earliest Acheulean assemblages not only in India but arguably also in Asia," Dennell tells Shaastra. He also points to the current knowledge that some artefacts discovered in China are dated to 2.1 million years ago.

From this site, Pappu's group also collected phytoliths, which are tiny particles of silica found in plants, especially herbs and grass. Phytoliths cannot be seen with the naked eye. They lend strength to leaves and make it difficult for herbivores to chew them. For instance, blades of grass are difficult to chew. When the plant dies and the decayed material becomes part of the soil, the phytoliths are incorporated into this. Like pollen, phytoliths recovered from soil sections or sediment cores are 'microfossils'. "They serve as biological proxies of the plant that produced them in the past," says K. Anupama, researcher from the Laboratory of Palynology and Paleoecology at the French Institute of Pondicherry. Anupama, along with Rathnasiri Premathilake of the Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka, helped Pappu's team analyse the sediment for phytoliths (bit.ly/Attirampakkam-Site) in 2017. Based on the study of phytoliths, the group was able to assess the vegetation that grew in the area several millennia ago. From this, they deduced whether the land had waterbodies or was dry. "Understanding the past holds the key to both the present and the future," says Anupama. This has to be done scientifically, based on data painstakingly collected, from the field to the lab to the microscope. "This and the interdisciplinary exchanges are what motivated me," she says.

IMPORTANCE OF DEBITAGE

Kumar Akhilesh points out that the stone tool trail conveys to the experienced eye a picture of the times. Not just the tools but also the debitage, or the materials discarded when a tool is made — such as powdery residue, chips of rock and leftover cores — throw light on the practices of the times.

Human behaviour can be inferred by an analysis of the tools, too, as stone tools are a result of human behaviour. Pune-based archaeologist Sheila Mishra, who worked in Western Maharashtra and has retired from Deccan College, Pune, explains that the tools show evidence of how early humans selected raw material, made and used a tool, and then discarded it.

One of the puzzling aspects of Attirampakkam was that it did not have any signs of debitage. There were no discarded flakes, and Pappu's team did not come across any powdery remains even when they carefully sieved the sediments and scrutinised them under a magnifying glass. It indicated that the denizens of Attirampakkam did not make the tools there.

Mishra sees similarities between Attirampakkam and the African sites. The oldest of the tools dated at Attirampakkam are Acheulean and have ages comparable to those of the Acheulean sites in Africa, she points out. Before the Acheulean in Africa, the tools were called Oldowan — the name derived from the Tanzanian Olduvai Gorge, known for its rich fossil and stone tool discoveries. Oldowan tools have been found throughout East Africa and also in Northern Africa, dating from 2.6 million to 1.8 million years ago. At the time of the Oldowan tools, the ancient humans in Africa belonged to the Australopithecus genus. Homo erectus is associated with the earliest Acheulean tools. Mishra explains her observation that these Oldowan tools in Africa were made perhaps not by the Acheulean people but by others, possibly earlier.

This would open the possibility that the Acheulean culture found its way not from Africa to India, but the other way around. Logically, there are three possibilities. The first is that early hominins learnt the art of tool-making in Africa and brought this knowledge with them to the rest of the world. Second, the hominins did come from Africa to other parts, but the art of tool-making was contemporaneously discovered in different places — for example, in India, simultaneously with Africa. Third, they may have thrived independently in India and Africa, made their tools and developed. Or even learnt tool-making in India and taken the knowledge to Africa.

Which of the above has the most substantial evidence? "The available evidence currently supports the first model," says Mohamed Sahnouni, Professor and Research Programme Co-ordinator, Archaeology, National Center for Research on Human Evolution, Spain. Sahnouni's group has made significant discoveries, providing evidence of several early hominid occupations, including stone tools and cut-marked bones dated to 2.44 million years ago and 1.92 million years ago at Ain Boucherit in north-eastern Algeria, as well as the earliest Acheulean stone tools in North Africa, dated to 1.67 million years ago.

There are "solid reasons" why he believes in the first possibility — "...early hominid fossils, early stone tools, and the first cut-marked bones (have been) found only in Africa so far," he says.

MORE WORK ON THE ANVIL

Pappu's team, meanwhile, carries on with the hunt. The researchers had surveyed some 8,000 square kilometres in northern Tamil Nadu and published the results in 2010. Fieldwork, conversations with people, and satellite remote sensing, for which they teamed up with the Indian Space Research Organisation, gave them several potential sites to work with. From these, they chose Sendrayanpalayam, and started excavations there in 2018. "One site cannot give you the answers. You need to know how people moved across the landscape," Pappu says.

In this new site, too, they have found stone tools and artefacts. In fact, they found more than just the tools. "We found evidence of artefact manufacture," says Pappu.

Currently, these are being dated, and the results of the analysis are being awaited. It remains to be seen if this discovery will alter the global understanding any further.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH