Planets' progress

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 05 issue 01 :: Jan 2026

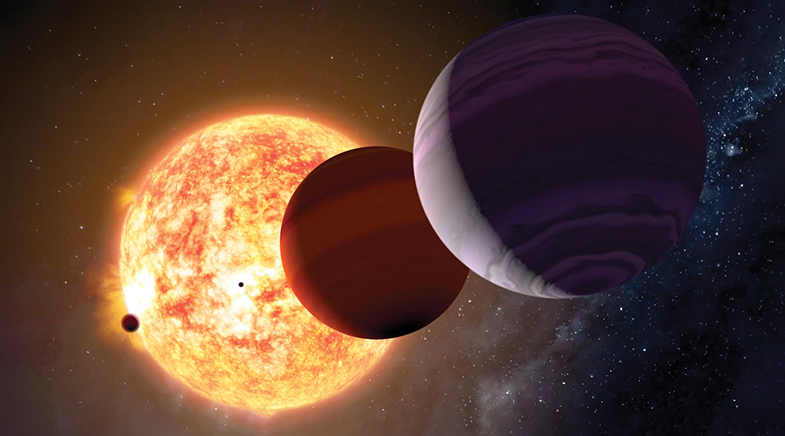

A rare glimpse of a stage of planetary evolution may help fill gaps in some cosmic theories.

For nearly a year, astronomer Joe Ninan pored over data representing starlight, or photons, that had travelled 354 light-years from a star to a telescope at Arizona's Kitt Peak National Observatory. He was looking for dips that would betray the presence of planets; in the study of planets beyond the solar system – exoplanets – this is routine. At the right vantage angle, a planet orbiting a star causes a subtle, fleeting decrease in visible starlight.

Among some 6,000 planets discovered beyond the solar system since the mid-1990s, two types dominate: super-Earths and sub-Neptunes, accounting for 45-60% of exoplanets. A striking deficit of planets between 1.8 and 2 Earth radii has long puzzled astronomers, and hints at missing pieces in current theories of how planets grow, lose mass, and settle into their final forms. Ninan's quarry may offer a rare glimpse of how planetary systems evolve when young.

Ninan, Associate Professor at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) in Mumbai, is a member of an international team studying V1298 Tau, a young star (only some 20 million years old) that hosts four planets discovered in 2019. The team has observed over 40 such "transits" and calculated, with unprecedented precision, the planets' orbits and masses. All four are about as large as Neptune, which has 3.9 times Earth's radius. But the two inner planets have masses four and six times that of Earth; the two outer planets have 13 and 15 Earth masses.

Given their sizes, the planets are lightweight, implying compact rocky cores wrapped in thick atmospheres dominated by hydrogen and some helium – the main raw materials of stellar systems. Under the young star's intense radiation – extreme ultraviolet and X-ray emissions – the atmospheres are eroding, their gases evaporating, their layers thinning out. "We have a snapshot of an early phase of planetary formation not ever seen before," says Ninan. "The star is still sculpting the planets; they haven't reached their final mass or size yet."

Computer simulations tracing the future of the V1298 Tau system suggest this erosion will continue for another 100 million years, steadily reducing the planets' masses. In a study published in Nature (bit.ly/V1298-Tau), Ninan and colleagues from the U.S., Denmark, Japan, among other countries, predict that each planet will shrink to 1.5-4 times Earth's mass. The two inner planets are expected to become super-Earths, while the two outer ones will turn into sub-Neptunes, the two most common types of known exoplanets.

"How exactly different planetary sizes and masses emerge remains largely unresolved: our own solar system has neither super-Earths nor sub-Neptunes," says Ninan. Before exoplanets were discovered, astronomers believed that gravity, collisions and migration early in a system's history were sufficient to explain planetary architectures. That view began to shift in 2018, when astronomer Lauren Weiss, now at the University of Notre Dame in the U.S., and her colleagues analysed 909 planets in 355 multi-planet systems. They found that planets in the same system tend to be similar in size, an effect they described as "peas in a pod". The four planets orbiting V1298 Tau fit this pattern.

The leading explanation for the radius gap has been atmospheric loss: stellar radiation strips gas from some planets, leaving smaller, rocky super-Earths, while larger planets retain their atmospheres and become sub-Neptunes. "This is exactly what we believe is happening around V1298 Tau," says Ninan.

But additional influences may also be at play. In 2019, one U.S. team proposed that internal heating of the planet may drive atmospheric erosion. Another U.S. group last year showed through computer simulations that both planet types can emerge from debris rings within a young star's disc, reproducing both size similarity within systems and the radius gap. Together, these ideas suggest that radiation, internal heat, and birth-disc structure shape planetary evolution. "Systems like V1298 Tau provide a rare chance to test and refine theories of planetary birth," says Ninan.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH