Fuel for take-off

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 11 :: Dec 2024 - Jan 2025

The funding environment for deep tech start-ups has improved, but large fund-raises are still uncommon.

Anand Anandkumar set up Bugworks, a biopharmaceutical start-up, in 2016 in India and the U.S., knowing from the beginning that fund-raising would be difficult in India. The company had an ambitious plan to discover a new generation of antibiotics. So far, the company has raised $38 million in equity and $15 million in grants, most of it from the U.S. It added cancer drugs to its line of research later. After nine years of existence, it is still a start-up, still looking for funding abroad to develop its portfolio further.

The story of Bugworks comes up repeatedly during discussions on funding deep science start-ups in the country, especially in biotech, but it is gradually becoming an exception rather than the norm. The company's sobering experience was primarily because of the unusually risky and difficult terrain in which it operates. The overall funding for deep tech start-ups has improved during the last decade, and especially in the past few years. Deep tech companies with a good business model and good technology can hope to get venture funding, especially in the early stages, unless it is in an exceptionally ambitious and risky business.

Early-stage funding in deep tech start-ups reached a five- year high in 2023, with $732 million being invested. This indicates a growing interest in new ventures.

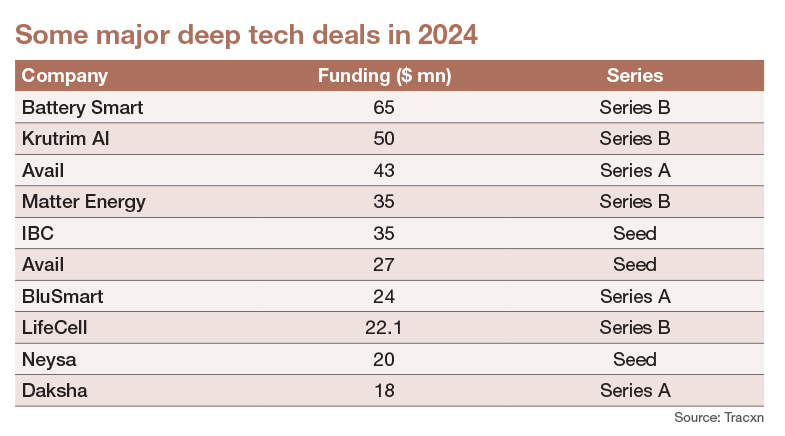

From 2014 to 2022, the total funding for deep tech start-ups in India showed a consistent rise, peaking at $2.21 billion in 2022. However, owing to the funding winter when venture capitalists (VCs) tightened their purse strings worldwide, funding in India's deep tech space decreased drastically in 2023. Despite lower total funding in 2023 and 2024, the funding per round has remained relatively high, particularly in 2024, averaging around $5 million per round. This indicates that when investments are made, they are larger and perhaps more strategic, emphasising quality over quantity in deal-making strategies. The start-ups being funded are in areas such as space, energy, cell-based therapies, and so on – all of which are areas that have potential to create economic value.

According to Vishesh Rajaram, Managing Partner, Speciale Invest, an early-stage venture capital firm that invests exclusively in deep tech ventures, the issue with deep tech is the perception that it is capital-intensive and that the ventures have a long gestation period. This is mainly a conclusion based on big deals in the U.S. market, where deep tech companies raise large amounts of money very quickly. A recent example is the Boston-based Commonwealth Fusion Systems, a spin-off from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. It raised a Series B round of $1.8 billion from a clutch of investors in December 2021. It had been around only for three years till then.

India's deep tech companies do not raise such money. However, they are also trying to solve a different set of problems in a different environment, and therefore may not need as much money as their American counterparts. Studies by the start-up data platform Tracxn show that early-stage funding has consistently grown in India, peaking at $732 million in 2023. A recent Nasscom report, DeepTech Startup Landscape Report – 2023 (bit.ly/nasscom-deeptech), noted that early-stage funding in deep tech start-ups reached a five-year high in 2023 with $732 million being invested. Till September 2024, early-stage funding reached about $458 million. This indicates a growing interest in new ventures. Seed-stage funding too has remained relatively stable, averaging $180 million in the past three years.

However, big-ticket, late-stage funding showed a dramatic decline from $1.3 billion in 2022 to $99.8 million and a mere $8.17 million till September 2024. On the other hand, in 2023, start-ups raised more grant and debt funding. Debt funding increased to $110 million from just $34.9 million in 2022. It showed a minor decline in 2024, with $57 million raised this way. This indicates that investors are favouring lower-risk, early-stage ventures amidst broader economic uncertainties.

While early-stage companies do manage funding, observers believe that start-ups are not being formed in sufficient numbers. While the deep tech ecosystem in India is considered to be in its early stages, according to Karthee Madasamy, Founder and Managing Partner of the early-stage venture fund MFV Partners, it is not necessarily nascent because deep tech is inherently global. "To make scientific or engineering breakthroughs that transform industries, there needs to be enough talent. While India has a wealth of technological talent, it also needs to get more talent going down the PhD path to drive deep tech start-ups forward," he adds. According to Naganand Doraswamy, Managing Partner, Ideaspring Capital, the pipeline of deep tech ventures in India is not as robust as it should be because of the low number of PhDs from Indian institutions.

There are some sectors where start-ups find it easier to raise money. According to Tracxn data, Indian space tech start-ups have raised upwards of $500 million. Hyderabad-based Skyroot and Chennai-based Agnikul Cosmos are top of the pack and have raised $99 million and $42 million in equity funding, respectively. One of the reasons behind space tech's success in India is the innovative work that the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has done in recent years. "Once you got the innovative work along around that industry, a lot of deep tech innovative companies have come up, which are getting some funding," says Mahesh Pratapneni, Founder of MedGenome, a genetic diagnostics company in Bengaluru. Sectors like biotech do not have such a pedigree.

"Ten years ago, no deep tech start-up was raising a large investment round. But it happens now. These start-ups have set a precedent that it is achievable," says Chirag Gupta, Managing Partner of 8X Ventures. He points to two other changes in the past couple of years in the venture fund space: first, the secondary market in the deep tech innovation space is starting to open up; and, second, the small and medium enterprise (SME) listing market, too, is opening up.

Secondary markets make it easier for VC firms to get their money back. For example, if a VC firm invested in a start-up for six years and wants to take an exit because it is at the end of its fund life, other larger funds, or family offices, or individual investors can buy out the VC firm's stake. Before 2020, there was no such opportunity, and the only way to get the money back was either through an IPO or through acquisition, says Gupta. "In case you can't hit the secondary market, you can try an SME listing, which was not possible earlier."

Although these changes have improved the funding environment, large fund-raises are still uncommon with deep tech start-ups. "India is the third-best ecosystem when it comes to tech start-ups globally. But when it comes to deep tech start-ups, India is sixth-best," says Achyuta Ghosh, Head, NASSCOM Insights. "I think India falls apart when it comes to median ticket size investments." That is a problem waiting to be solved later in the decade.

See also:

Indian start-ups dive into deep tech phase

Start-ups born on campuses

Bridging the academia-industry gap

Support systems for start-ups

Space start-ups get into a higher orbit

Outlook positive

Chipping in

The rise of quantum.in

Automated growth

India is poised for a tech leap

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH