Indian start-ups dive into deep tech phase

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 11 :: Dec 2024 - Jan 2025

In their current phase, Indian start-ups are developing the knowledge and the skill to take themselves and the larger economy to a higher orbit.

The Center for Non Destructive Evaluation (CNDE) was set up in IIT Madras in 2000 to develop technologies for monitoring industrial products and processes. Aircraft, high-speed trains, heavy machinery in factories, and several other critical products need constant monitoring even as they continue to do their jobs in the field. CNDE's aim was to develop leading-edge expertise in non-destructive testing, and apply it to improve industry. Start-ups began forming from the CNDE soon after it was set up. Their number now stands at 10. One of the recent start-ups, XYMA Analytics, was built on a foundation of 25 years of technology development.

XYMA Analytics uses industrial Internet of Things (IoT)-enabled ultrasonic waveguide technology to continuously measure critical parameters such as temperature, viscosity, density and fluid levels in process industries. The technology was complex, and required the development of multiple areas like sensors, artificial intelligence (AI) and IoT. However, it was not just the development of technology that took time. The market for its products itself got ready only recently. "We have done field trials with all the big names," says Krishnan Balasubramanian, who heads the CNDE. "We are seeing the market is coming to us instead of us going to the market."

Indian deep tech companies of today operate in diverse sectors that are vital to the economy, including aerospace, healthcare and agriculture.

Although the two are not directly related, the growth of the CNDE somewhat mirrors the growth of India's deep tech ecosystem. At the turn of the century, the technology start-up culture was not fully formed in the country. The initial set of software companies had made a name for themselves, in the process creating a set of wealthy people who themselves were motivated enough to start companies. The second generation of companies were also driven by software, but chip design had shown enough promise by the turn of the century. The first decade and a half was dominated by internet start-ups, who executed business models tried elsewhere: Flipkart took the cue from Amazon, Paytm from PayPal, and Ola from Uber, and so on. However, this period was also giving birth to India's first generation of deep tech start ups.

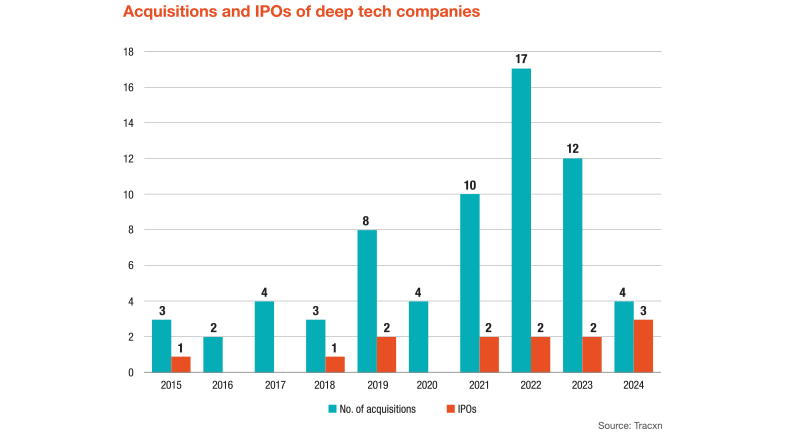

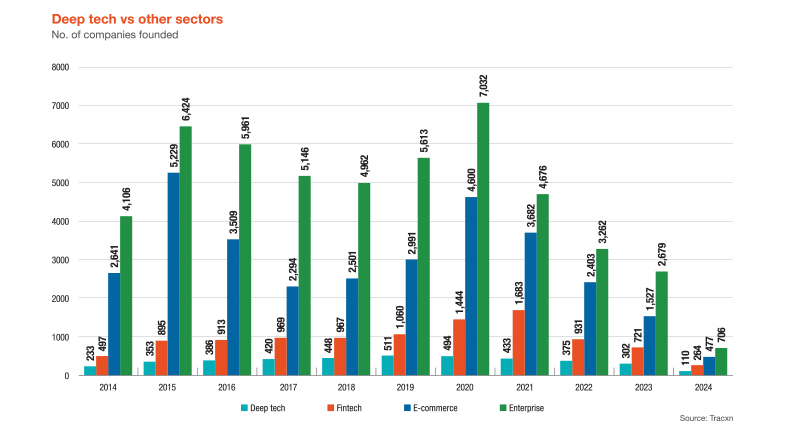

These companies were not noticed by the wider public initially, but they inspired the current generation of deep tech start-ups. Strand Life Sciences was set up in 2000 by four professors at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc); its big investors exited in 2021, when Reliance Strategic Business Ventures bought a strategic stake in the company. Tejas Networks was also set up in 2000, with a key founder coming from IISc, and Tata Sons bought a large stake in the company in 2021. ideaForge, set up by IIT Bombay graduates in 2007, had its IPO in 2023. The success of these companies (see graphic) and others has now persuaded investors that Indian industry has entered the deep tech phase. "In some ways," says Vijay Chandru, Co-founder of Strand Life Sciences, "it is an indication of the arrival of a market. India was (earlier) not a viable market for deep tech innovations from a commercial point of view."

SHOWING PROMISE

Several companies that were born in this decade satisfy the working definition of deep tech: a company with unique technology that can take at least two years, if not more, to replicate for a competitor. Such companies also solve problems that are seemingly intractable. Some deep tech companies like Google or Amazon can have an outsized influence on a country and the world, but many smaller companies have been equally transformative. This is what the deep tech phase in India promises to be over the next decade, because of its breadth and depth.

To begin with, the Indian deep tech companies of this decade are quite diverse. They are also present in sectors that are vital to the economy: aerospace, healthcare, drug discovery, robotics, agriculture, energy, semiconductors, quantum computing. The earlier generation of companies have established a base and reputation in these fields. Unlike that generation, the current start-ups have a good support ecosystem in terms of infrastructure, funding, and support technologies. India is a large market as well, and it serves as a field to try globally relevant technologies at a low cost.

THE RIGHT CATALYSTS

A few events have combined over time to usher in this deep tech phase in India. The first is a natural evolution of tech industries, from services to software to internet companies to deep tech. In life sciences and healthcare, the path was from generics to services to true innovative products. This journey was never smooth or linear. Deep science companies suffered from lack of funding, especially for expansion, and had to move base abroad to secure funding. Often there wasn't enough experience in the country for scaling such companies or easily available equipment for research work. Such problems slowed down the growth of deep tech companies, but didn't stop them from forming, especially in the last decade.

Academic institutions took a while to set up incubators and research parks and the right framework for their faculty to form start-ups.

The second event is the rise of genuine academic start-ups, those that have been built like XYMA on long years of research. Academic start-ups have had their own evolutionary path: they have often been slow to take off as institutions took a long time to set up incubators and research parks and the right framework for their faculty to form companies (Start-ups born on campuses). The country's premier research institutions were also slow to reorient their research towards industrial problems, from a culture of publishing to a culture of applied work. Indian public research institutions had a decade of low funding, which had forced some of them to rethink their strategies, and especially to think of start-ups as respectable enterprises. "There are so many things we do well because of these start-ups," says Balasubramanian. They bring new problems and sometimes help faculty solve them. Start-ups have facilities that the faculty do not have sometimes. "It has helped us retain talent in deep tech, which normally would have gone elsewhere," he says.

APPETITE FOR RISK

The third reason for the formation of the deep tech phase is the increasing tendency of young entrepreneurs to take risks, as the first and second generation showed the rewards that accompany the risks if they can be managed. This tendency to take risks after the success of previous generations, with the acceptability of failure, and with the increase in disposable incomes and infrastructure support to mitigate risk. In this, they have been helped by many incubators and research parks (Support systems for start-ups). "Technology de-risking is an extremely important area for deep tech incubators," says V. Premnath, Director of the Venture Center at the National Chemical Laboratory, Pune.

The fourth reason is the improving technical capability of scientists and engineers. For three decades, scientists and foreign universities have shown a willingness to return to India in slightly larger numbers than before. Successful entrepreneurs abroad have funded advanced facilities in research institutions, especially the Indian Institutes of Technology, thereby allowing the faculty to research contemporary problems and train students on them. Three decades of multinational development centres have created a large pool of highly skilled engineers in some key areas, the most significant of these being in chip design. India has the world's second-largest pool of chip designers (after the U.S.), and their expertise feeds into several start-ups and larger technology companies.

A tendency to take risks, along with a readiness to take failure in their stride, is what materially characterises the emerging generation of entrepreneurs.

As all of these came together, and software became less attractive for investment, venture capitalists (VCs) became more willing to invest in deep tech. The transformation of attitudes has been swift. "In the VC world, nobody wanted to put money in deep tech three years back," says Ganapathy Subramaniam, a seed investor in ideaForge, and Founding Managing Partner of Yali Capital. "Now everybody wants to put money in deep tech." Government schemes in various areas provided seed money to aspiring entrepreneurs, but entrepreneurs had struggled through the last decade to go beyond grant money to the first VC investment.

"There is a shift in the funding environment," says Y.N.S. Harshita, Incubation Manager at ASPIRE-BioNEST, a deep tech incubator at the University of Hyderabad. In her interactions with investors, she has noticed that if they are convinced about the entrepreneur's idea and persistence, they are ready to invest.

HOME AND THE WORLD

Start-ups are of two kinds: companies that try to solve a global problem, and hence are not dependent on location, and those who solve problems of developing countries using advanced technology. Many potentially global companies first develop technology for the Indian market, and then take it to the rest of the developing world. The Bengaluru-based Niramai Health Analytix, set up in 2016, has a software-based medical device to detect breast cancer at an early stage, by using thermal screening combined with patented machine learning algorithms to detect breast cancer reliably and accurately. Niramai's screening method is available in about 30 cities in India and in the UAE, Kenya, Sweden, Turkey and the Philippines. The company has also received U.S. FDA clearance for its first device, SMILE-100, which is a breast thermography device. "If you innovate in a resource-constrained environment," says Niramai Founder and CEO Geetha Manjunath, "you develop something that is of lower cost than the existing methods. If you prove it to be accurate, useful and people like it, every country wants to save money."

Several deep tech companies are aware from the beginning that their biggest market is outside India. INDIUS Medical Solutions, also set up in 2016, went to the U.S. right from the beginning. According to Aditya Ingalhalikar, Founder and CEO of INDIUS, a presence in the U.S. was necessary if the company was to tap the market, as the U.S. accounts for over 60% of the $14 billion global spinal implants market, and India is a mere 2%. This awareness drove quality of the product from the beginning. Companies like INDIUS, which think global right from the beginning, attract a subset of investors who are not interested in building companies in specific countries.

"If an Indian deep tech start-up solves a significant problem, customers will be everywhere," says Karthee Madasamy, Founder and Managing Partner, MFV Partners, a San Francisco-based venture capital firm that invests in deep tech ventures. Naganand Doraswamy, Managing Partner of the Bengaluru-based Ideaspring Capital, says that his VC firm will not invest in ventures that have only an India presence. Many recent deep tech ventures are of this category that think global from the first day.

DEEP LOCAL ROOTS

The second category of deep tech companies look specifically at Indian problems or adapt an existing complex technology to an Indian situation. The healthcare, agriculture and social sectors have several such start-ups that try to lower the cost of healthcare by making cheaper devices or solve problems that do not exist in developed markets. Some early examples of this kind – not always in deep tech – include 5C Network, Ergos, and Solinas Integrity. The Bengaluru-based 5C Network provides radiology services across the country. Ergos helps farmers convert their grains into digital assets. Solinas, a true deep tech start-up, uses complex fluid dynamics modelling to reduce water contamination. A recent example is Metastable Materials, a company with the technology to extract critical metals with minimum environmental impact. Uravu Labs, also in Bengaluru, develops atmospheric water-capture technologies.

One category of deep tech companies looks specifically at Indian problems or adapts an existing complex technology to an Indian situation.

Such companies could add significant value to the economy. "Look at Israel, where there is significant technology powering their economy," says A. Thillai Rajan, Professor in the Department of Management Studies at IIT Madras. "It's a dry area so they have developed tech to make agriculture more productive." Climate resilience, for example, needs the development of crops popular in India that can withstand extreme weather expected to be common over the next few decades. The ever-present danger of pandemics requires the ability to respond quickly with diagnostics and treatments. The extraordinary amounts of waste generated in the country may require special techniques to handle, especially in toxic dumps that have surrounded most Indian cities. Water resources will be stretched thin with increasing heat. A large range of start-ups is already trying to solve these problems.

These problems are so intractable that they require deep science and tech to solve. The current breed of entrepreneurs is best placed to solve them. The ecosystem has matured enough to support them as well.

See also:

Fuel for take-off

Start-ups born on campuses

Bridging the academia-industry gap

Support systems for start-ups

Space start-ups get into a higher orbit

Outlook positive

Chipping in

The rise of quantum.in

Automated growth

India is poised for a tech leap

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH