Blood vs blood

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 05 :: Jun 2024

The discovery of different blood groups made transfusions safe.

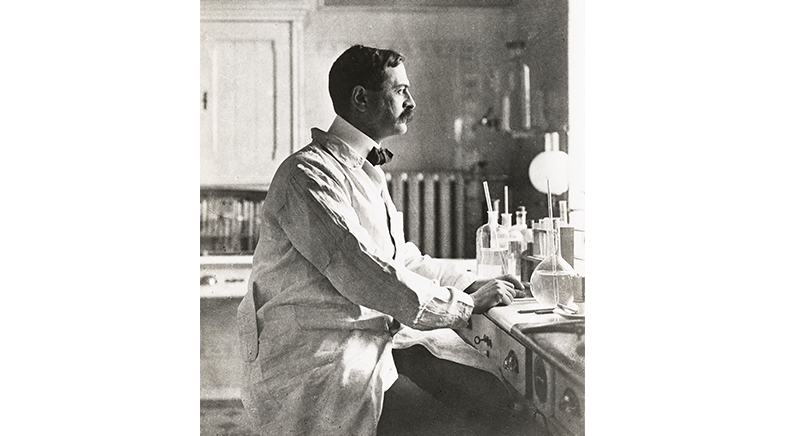

A footnote in a paper published in 1900 ended up saving millions of lives – and counting. Its author, Karl Landsteiner, was an assistant at the University of Vienna at the time. After studying medicine and working with several European scientists, he had joined the University's Department of Pathological Anatomy in 1898. Besides dissecting cadavers, he took a keen interest in blood chemistry, noticing that blood serum from a healthy human caused animal blood cells to clump together.

In the footnote of the paper (bit.ly/Karl-1900), which described the effect of serum and lymph fluid on bacterial enzymes, he noted that human serum could also cause clumping of blood cells from other, healthy humans. Doctors had seen such clumping before – during unsuccessful blood transfusions from which recipients died – but they did not know why it was happening. Drawing his own blood and his colleagues', Landsteiner decided to investigate this.

What he found (bit.ly/Karl-1901) was that only some combinations of blood and sera caused clumping. He guessed that a specific antigen on the surface of blood cells differed between individuals, and divided the samples into groups based on whether they carried antigen A, antigen B, or neither (group C, which later became O). Mixing group A sera with group B blood cells, and vice versa, caused clumping. No clumping happened when group C blood cells mixed with A or B sera. But group C sera caused clumping of both A and B blood cells. His students also discovered a fourth group (AB) containing both antigens.

A NOBEL? MEH

Landsteiner was extremely publicity-shy. He was also a tad disappointed when he received the Nobel Prize for his work on blood groups – which he felt anyone could have discovered – and not for the research on haptens. He suggested that the Prize should have gone to another scientist, Thomas Hunt Morgan, instead. He didn't even inform his wife and son, who only learnt about it from a friend who came home to congratulate him (bit.ly/Karl-history).

At first, Landsteiner wasn't sure how useful these findings were. Perhaps the police could use them to match blood samples from crime scenes, he thought. But just before the First World War broke out, scientists found a way to store blood for days using a citrate anticoagulant (bit.ly/Karl-tribute). Donors and recipients didn't need to be next to each other anymore, and could be matched using Landsteiner's classification. Blood transfusions started en masse, saving countless lives.

The ABO classification, for which Landsteiner received the Nobel Prize in 1930, was only one of his many contributions. With dermatologist Viktor Mucha, he found that dark-field microscopy could help identify syphilis-causing bacteria – a method used even today. In 1908, using spinal fluid from a boy who died of polio, he and Erwin Popper showed that a virus was the causative agent. In 1921, in what he thought was his crowning achievement, he showed that some molecules called haptens ("half-antigens") only trigger an immune response if they are fastened to a larger protein carrier. In 1940, Landsteiner and Alexander Wiener discovered the Rh factor, an inherited protein that can cause complications in pregnant women.

DOGGED IN THE LAB

Landsteiner was also a notorious perfectionist. While carrying out experiments, he would ask an assistant to stand by, as he spelled out each step. When a discovery came to light, he would instantly dismiss it and do the experiment again, just to be sure it really happened. He would also ask his understudies to repeat their experiments again in front of him.

Landsteiner continued doing research even after retirement. When his wife developed thyroid cancer, he spent the last few years of his life seeking a cure. On June 24, 1943, he suffered a heart attack in his lab and died two days later. His birth anniversary, June 14, is now celebrated as World Blood Donor Day in honour of his life-saving work.

Ranjini Raghunath is a Bengaluru-based science writer and editor.

See also:

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH