The artful storyteller

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 issue 06 :: Nov - Dec 2022

Siddhartha Mukherjee has crafted a literary biography of the cell, disease, scientists, patients, colleagues, relatives, and of himself.

Just as matter is made of atoms, life is made of cells. All biology at the level of the whole organism can be explained in terms of cell biology. Siddhartha Mukherjee, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Emperor of All Maladies, uses this simple truth as the underlying (and sometimes tenuous) thread connecting a wide range of subjects in his latest book, The Song of the Cell.

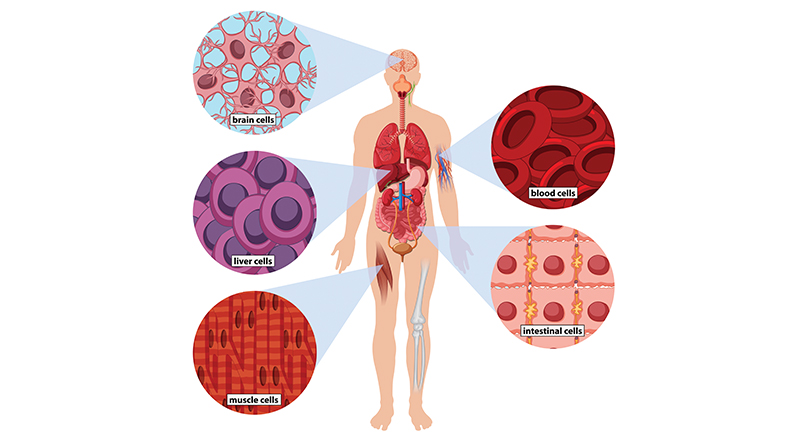

This is not a book about the cell's internal world: he spends a fleeting 13 pages on that topic. Instead, this book is about the varieties of cells that make up our bodies, starting from how a fertilised egg becomes a whole person made up of an estimated 30+ trillion cells. These cells encompass a fantastic range of functions: from reproduction (zygote) to blood circulation (blood cells) and from thinking (neurons) to defending the body from invaders (immune cells). Occasionally, cells trip and form cannibalistic tumours (cancer).

It sounds incredible that humans were peering down microscopes for over 100 years before it dawned on them that living tissue had a cellular structure. And that realisation birthed the theory that all living matter, plant or animal, was made of cells. But where did cells come from? In the 1800s, cells were thought to arise through a process akin to crystallisation from biological fluids. But, as the Greek philosopher Parmenides said, ex nihilo nihil fit: nothing comes from nothing! And sure enough, German physician Rudolf Virchow, following the trail of evidence scattered by his predecessors, showed that all cells come from cells: Omnis cellula e cellula. Virchow also presciently added that diseases of the body are diseases of cells.

Mukherjee paraphrases Virchow by writing: "To locate the heart of normal physiology, or of illness, one must look, first, at cells." And Mukherjee takes the liberty to roam freely across the landscape of human biology. Now and then, like a beach collector examining an interesting shell, he stops to pick up an intriguing piece of human cell biology and uses it to expound a larger science story.

SIMPLY ELEGANT

In this book, the cell is the protagonist. There are hundreds of cell types in our bodies. Each is unique in appearance and function. Mukherjee tells the tale of the cell by expounding on a few archetypes from among the many. The choice of cell type is biased in favour of what he is familiar with as a haematologist: six chapters are devoted to blood cell types. His research into the cause of osteoarthritis is superbly narrated. The only other cell types he attends to in any detail are the nerve cell and the insulin-producing pancreatic beta cell. He has a whole chapter on germs and germ theory, but only half a page for the liver cell. His choices are idiosyncratic.

Early pioneers of cell biology used the newly invented microscope to 'measure the world by eye'. Finding patterns through careful observation was enough for these pioneers to infer cell theory. But more often than not, it is the clever and elegant experiment that answers an important question. And Mukherjee's lucid prose brings these experiments to life.

For example, what drove single cells to evolve into complex multicellular organisms? That question was behind a "magnificently simple" experiment done by a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, William Ratcliff. Ratcliff grows generations of yeast in flasks. Between each generation, he selects cells that naturally form clusters and sink to the bottom. By the end of the experiment, this process of repeatedly selecting them for this trait and growing them yields yeast cells that prefer to form multicellular clusters: "selection for multicellularity in a flask!" After thousands of generations, the cells became even more connected, in some instances dissolving the walls in between. Mukherjee hypothesises that such multicellular clusters are preferred during natural selection because they allow cells to specialise and improve overall organismal efficiency.

Another example that Mukherjee enlivens with his prose is the question of how fat in cell membranes is arranged. Is it a single layer of fat, or is there more than one layer? Physiologists Evert Gorter and Francois Grendel extract fat from a predetermined number of red blood cells. They then spread the fat in a monolayer and determine that the area of spread is equivalent to twice the surface area of the cells, leading them to the conclusion that the cell membrane is made of two layers of fat. There cannot be a more direct and simpler way to arrive at this conclusion.

TELLING TOOLS

Mukherjee uses all the artful storytelling tools that won him the Pulitzer for his first book. His style is not so much like the peeling of an onion as it is like a heart surgeon who reaches into the chest to pull the heart out. His narrative moves friskily from highlight to highlight. He serves up well-known stories with a fresh coat of word paint. In his retelling, the stories embellished with the choicest bons mots and metaphors bloom afresh. "...death isn't a flying apart of organs. It is a withering grind of injury set against the ecstasy of healing." Poetic. Like Diwali lights strung together: elevating the prose, while at the same time illuminating the science. The good thing is that he does not attempt completeness just for the sake of it. He simply dips into the interesting parts and then moves on.

Mukherjee's style is not so much like the peeling of an onion as it is like a heart surgeon who reaches into the chest to pull the heart out.

He weaves in stories of people — their peccadilloes and peculiarities revealed — to add drama. One scientist is made out to be "skinny and boundlessly enthusiastic", and another is described as "In his blue jacket and tie, Sandel looked manicured and professorial" — which makes for vivid imagery, although the BMI of a scientist or his dress sense should have no bearing on the story! Even cells are given personas ("the sperm's frantic efforts to reach the egg"), though Mukherjee does anticipate criticism and excuses himself with the disclaimer: "To be clear, cancer cells don't possess sentience".

ONE IN ALL

Sometimes the storyteller becomes the story when he interpolates biographical detail into the narrative. Anyone who has read his books cannot but be familiar by now with the familial ailments in the extended Mukherjee clan. In this book, he introduces his depression as a way to illustrate how cells in the brain work. The Song of the Cell is not simply a well-crafted commentary. Instead, it reads like a literary biography of disease, scientists, patients, colleagues, relatives, himself and the cell, all at once.

What some readers may miss in the book is detail on the coming age of cell therapeutics as well as topics at the expanding edge of cell science (such as exosomes, phase separation). While some readers may be happy being entertained by Mukherjee's wordplay while being shown familiar terrains in closer detail, others may want to go to places they have never been before. Mukherjee's idiosyncratic selection of topics means that the contents look like a stamp collection: the most colourful stamps get the most attention, whether they contribute to the overall theme of the book or not. The story of the renegade Chinese doctor, who uses CRISPR to edit the genes of babies, is a case in point. It does not belong here and seems to have been incorporated solely because it was an easy story with which to grab the reader's attention. And then there is a whole chapter on COVID-19 (an already overexposed topic on YouTube and JAMA). He does make an apologetic remark on the introduction of this topic. But it does seem like a contrivance he might have avoided. This material detracts from making the book a solidly coherent whole.

His prose is like Diwali lights strung together: elevating the text, while illuminating the science.

Has Mukherjee outdone his first effort? I do not think so. But he has certainly written an eminently readable and entertaining book. Even if you knew much of the stuff already, hearing it in Mukherjee's lofty and luminous prose will make it seem like you are hearing it for the first time. Definitely, a book worth reading.

A clinical pharmacologist and neuroscientist, Dr Swami Subramaniam is CEO of Ignite Life Science Foundation.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH