Why big science spends must go on

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 edition 02 :: Jul - Aug 2021

This is as good a time as any to look deeply into the significance of all our activities and the rationale for doing them. In troubled times, people tend to focus on the truly important and meaningful, leaving other activities to more sanguine periods when we have plenty of time and money. This is as true of corporations and governments as of individuals. At a time of serious financial crunch, what are the activities that the government should support? In science, which is the purview of this magazine, what kind of research is worthy of funding?

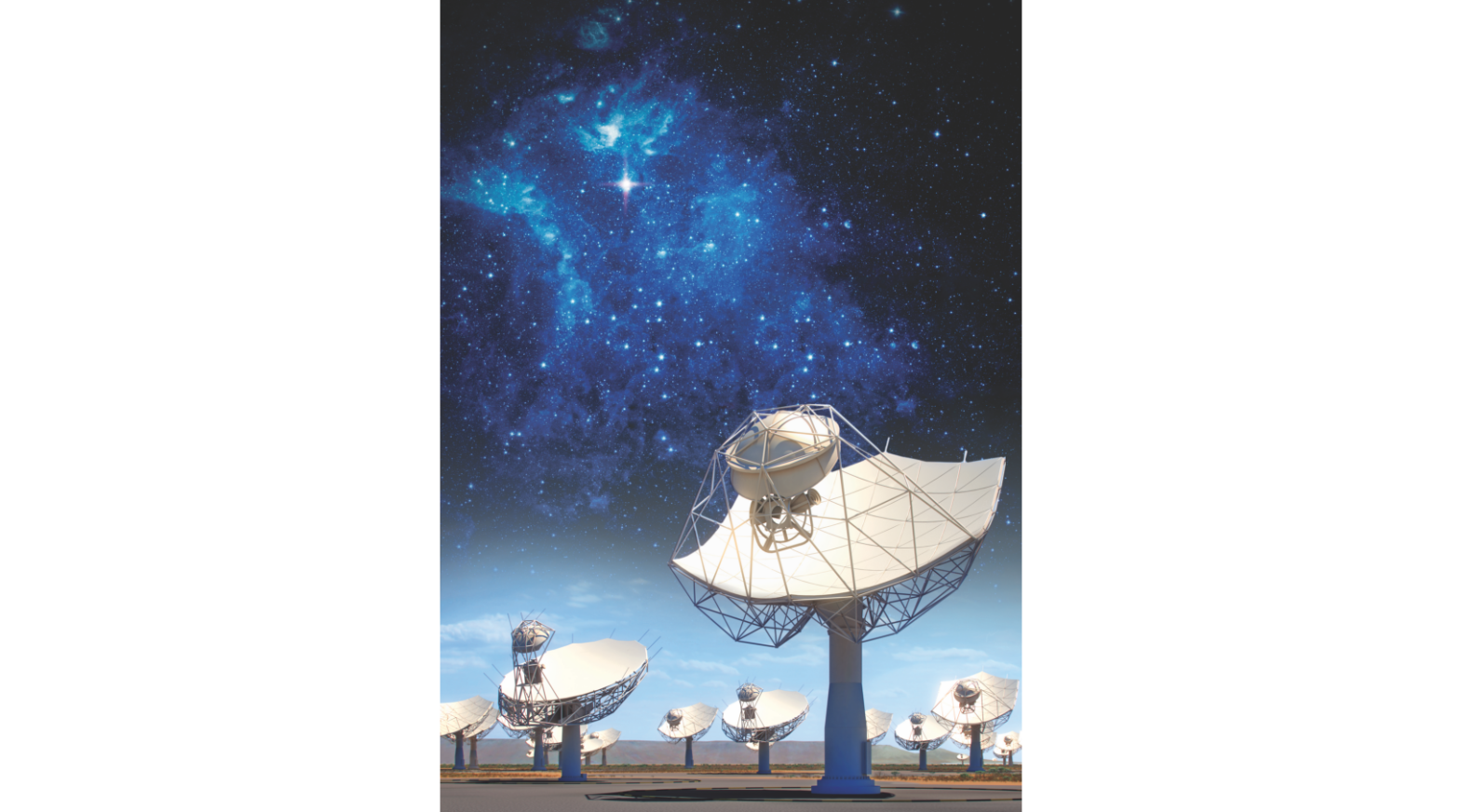

This is an old question and will be asked again and again throughout this century, and probably in the next century as well. However, at a time when COVID-19 has depleted government coffers, the public has a right to ask whether expensive blue-sky research should be funded. Of what use is high energy physics or cosmology or astronomy to the public? A state-of-the-art telescope can cost a billion dollars. Setting up a particle accelerator will cost several times as much. The running cost of a large accelerator can be a billion dollars a year.

This is why even rich countries are collaborating to do big science. Although collaboration can bring down the cost of the project for each country, it is still expensive for the participants. Should a middle-income country like India spend substantial money to participate in a big science project? India is now participating in six multi-billion-dollar science projects, each costing the country more than ₹1,000 crore, apart from working on one of its own. What will the taxpayers get in return from them? It is not an easy question to answer, and our cover story is about the possible answers.

Pallab Roygupta talks to scientists in several laboratories and private companies to investigate the benefits of big science, both intellectual and commercial. As he reports, the benefits are not easy to pin down in the short term but substantial in the long term, as big science projects generate technology for the future. For private companies, exposure to technology early in their development can mean a good high-tech business a decade or two later.

Spending on big science projects yields substantial benefits, even if only in the long term: these projects generate technology for the future.

In Diagnosis at your doorstep, Gauri Kamath reports on the possibilities of point-of-care diagnostics. In a country with a substantial rural population, often in places far away from cities and towns, centralised testing can delay the diagnosis of serious diseases. However, as she says in her story, "conventional technologies were not designed for rapid turnaround or distributed deployment." Newer technologies promise to change this situation and help cure or better manage serious diseases through early detection.

On other pages, we also look at India's options in tackling climate change, the improving science behind weather forecasting, the success of the KIIT business incubator in Bhubaneswar, and the lure of lab meat. Rapid climate change is the defining problem of this century, and the world is not responding rapidly enough. We have a set of stories and graphics on the problem. T.V. Padma gives the background for the IPCC Report and the Conference of the Parties in November; the graphics of India’s bumpy road to ‘net zero’ capture India's path so far and the possible future in renewable energy; our guest columnist Rahul Tongia writes how India should reassess its options in pricing, regulation and innovation.

As the earth warms up, and the weather becomes unpredictable, it becomes more and more important to predict it accurately. India has invested, through the monsoon mission, heavily on weather forecasting. The country has high-performance computers and an improved network for collecting data. However, the science that drives weather is not understood very well. In It’s raining weather models, Mywish Anand writes about how the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology in Pune is making progress in this regard.

In The ideas factory, Tazeen Qureshy writes about the rise of the KIIT business incubator, despite being located in a Tier-II city that did not have a good business ecosystem in its early days. The KIIT business incubator has now given birth to 230 companies, one of which is on the verge of becoming a unicorn. And, unlike other smaller towns, it is generating start-ups in high-technology areas. The future of technology start-ups is not just in the cosmopolitan cities.

Finally, in Steven Weinberg Death of a Star, Dilip D'Souza write about the physicist Steven Weinberg who passed away on July 23. He was not just another Nobel Prize winner. One of his papers, just three pages long, changed the way physics is practised.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH