Medical moonshots

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 05 issue 01 :: Jan 2026

ICMR's 'First-in-the-World' Challenge is a 'Eureka!' moment for bold ideas in healthcare innovation.

After over a decade of pursuing a research career abroad, Sarvesh Kumar Srivastava returned to India in 2023. He joined the Centre for Biomedical Engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Delhi, where he started an interdisciplinary research group. Coincidentally, that year India landed a rover on the Moon's South Pole, a global first. Inspired by the successful Chandrayaan-3 mission, the country's apex agency for biomedical research, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), decided to fund moonshots in healthcare.

Srivastava is among the beneficiaries of a pioneering ICMR award in 2025, which seeks to support disruptive and original concepts that have yet to qualify for conventional funding. He develops microscale devices that allow insulin to be taken orally by enhancing its absorption in the gut. An oral insulin could prove revolutionary for millions of people with diabetes, who have no choice but to inject insulin daily to control blood glucose (see 'Small is big'). To bring real change, researchers must push boundaries, says Srivastava. But such an approach demands intrepid backers. "You need someone who says: 'You go try. If you fail, no problem'," he says. "(The award) will help researchers push boundaries."

Launched in 2024, the 'First in the World (FIW) Challenge' research grant seeks to fund high-risk, high-reward healthcare innovations that could lead to products, technologies or solutions that are truly first in the world. The challenge is open to all: researchers at private companies are among those who have qualified. The review process is institution-agnostic — to ensure a level playing field and encourage innovation from all sectors, says Taruna Gupta, Scientist G & Head, Development Division at ICMR.

The funded ideas span a spectrum, including diagnostics and therapeutics. They aim to tackle intractable healthcare challenges such as diabetes, drug-resistant infection, and cancer.

A DIFFERENT LENS

The grant differs from traditional funding mechanisms in several ways, Gupta says. "It encourages bold, unconventional thinking rather than incremental research," she explains. "Proposals are evaluated on novelty, global first-mover potential, and anticipated impact." This focus on unsolved problems is a different lens from the usual, urging Indian scientists to lead rather than to follow, says Utkarsh Palnitkar, an independent life sciences consultant who has advised and been closely associated with Central and State government initiatives to boost healthcare innovation in academia and industry. "It will provide an impetus to look at novel research, which has always been a challenge in the country."

At the University of Delhi South Campus, it led Amita Gupta and her team, for instance, to think out of the box and beyond routine research. The Professor and Head of the Department of Biochemistry won the grant for a rapid test that checks whether donated blood is free of a clutch of pernicious infections (see 'Green signal for red').

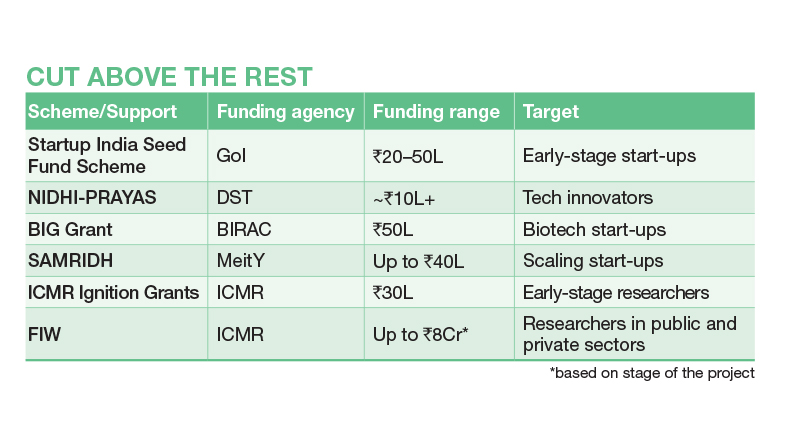

The FIW Grant amounts are significantly higher than typical grants, in crores of rupees rather than lakhs (see table: 'Cut above the rest'). The aim is to de-risk early innovation and accelerate translation while pushing the frontiers of medical science. Researchers are funded to develop demonstrable prototypes and to create a readiness for regulatory pathways or commercialisation. This could be a lifeline for start-ups that are too early in the product lifecycle to attract private funding (also see 'Indian start-ups dive into deep tech phase'). "These kinds of grants are very, very helpful, to take the prototype to the product level," says Shailesh Govind Ganpule, Associate Professor at IIT Roorkee.

BEYOND THE CHEQUE

Palnitkar suggests wider promotion of such an initiative, such as by partnering with trade associations. More important, there should be clarity on how to move forward. "There have to be mechanisms of assistance beyond writing the cheque."

Many proposals articulate original solutions addressing unmet clinical needs, and show clear potential for global leadership, says Gupta of ICMR.

Shaastra chronicles a few that made the cut.

LEVEL UP IN BUG BUSTING

Boosting immunity to tackle infection.

When threatened by bacteria, fungi and viruses, the body's first line of defence is to send out soldiers of the innate immune system to fight them. If a cut finger heals without getting infected, it is partly because of proteins that go by the rather literal moniker of Host Defence Peptides (HDPs). Mukesh Pasupuleti, Senior Principal Scientist at Lucknow's Central Drug Research Institute (CDRI), has studied HDPs for over two decades. Given their broad anti-microbial properties, he recognises that HDPs could be turned into potent drugs to counter even life-threatening infection

These are expensive to synthesise. Their potency can lead to unacceptable side effects and trigger an undesirable immune response. Mostly injectables, they need a cold chain for storage and transport. Having pursued his doctoral and post-doctoral studies under Canadian and Swedish pioneers in the field of HDPs, Pasupuleti knew this. He decided to look for small molecules — chemical compounds taken orally that could activate the immune system to express more of these HDPs instead. An oral pill would have all the advantages of manufacturing, storage, transport and administration that injectables do not have. It would be relatively economical to produce. While these are not antibiotics, such drugs could be given alongside them as adjuvants to boost the body's innate immunity and counter drug-resistant infections. "These are possibilities, but I don't yet have the data, so I cannot claim it will work," he says.

Pasupuleti's team trawled a large global clinical trials registry to create a database of drugs that had cleared human safety studies. They had been shelved in later trials for reasons other than safety, such as the lack of efficacy in the specific disease area or use for which they were being tested. The advantage of this was that there was already some data on how they behaved in humans, potentially aiding speedier drug development, says Pasupuleti.

They listed 8,000 compounds that had been tested for a range of 'indications' or uses. They acquired the chemical structures of 6,000 of them either from publicly available information or from the companies behind those drugs. The next step was to design a laboratory test to screen the many compounds. The test uses human and mouse cell lines that are best suited for studying the innate immune response.

Since it serves as the basis for proof of concept, the test itself must be foolproof. The ICMR award will be used to validate the test and deploy it to identify molecules that could activate the overexpression of HDPs. Successful in vitro testing will have to be followed by animal studies. If one or more compounds clear these, they will have to be tested in specific infections, such as those of the skin. They may need industry partners for further development. "I am not expecting a cakewalk."

As microbes become increasingly resistant to antibiotics, the world urgently needs a variety of new and potent agents to face them down, as the drug industry's resources are flowing towards more lucrative disease areas such as cancer and obesity.

SMALL IS BIG

Creating microdevices for oral insulin absorption.

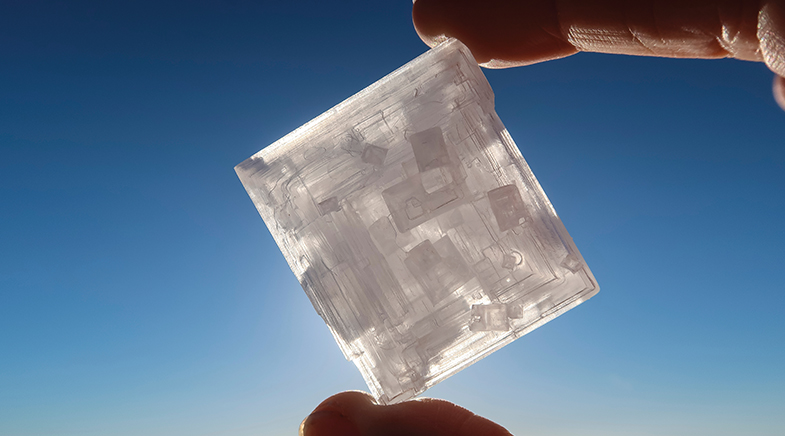

The peptide hormone insulin was synthesised over a century ago, but the only foolproof way of delivering it is still by injection. Attempts at alternative delivery routes — oral, inhaled, buccal — are yet to succeed. Researchers continue their efforts, leveraging new technologies in the hope of a breakthrough. One such effort is at the 3MLABS at IIT Delhi. 3M stands for Medical Microdevices and Medicine, an interdisciplinary group whose aim is to map the complex bioenvironment of the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract and to find ways to modulate it with therapeutics. M also stands for microbiome, the universe of microorganisms that inhabit the GI tract, says Sarvesh Kumar Srivastava, Professor and Group Leader at IIT Delhi's Centre for Biomedical Engineering.

A key area of research is self-organising microscale devices. Srivastava has won the ICMR FIW award to build and validate prototype microdevices to deliver oral insulin through the GI tract, the long tube that runs from the mouth to the anus, to maximise its absorption. Srivastava compares the underlying principle of self-organisation to the classic flapping bird made using the Japanese art of origami or paper-folding. "There is a trigger that creates an action," he says. "You pull its tail, it flaps its wings." Microdevices respond in a predetermined way to specific stimuli. These could range from chemical and electric to magnetic and wavelengths of light, among others.

The GI tract is an inhospitable environment for oral insulin, an unstable peptide that breaks down or alters easily. Stomach acids and intestinal enzymes degrade it. Then, what's left of it has to cross the intestinal lining: a terrain of peaks and troughs that is covered with a thick layer of mucus and tightly packed with epithelial cells. Only what falls over the mucus line moves down from the top of the intestine to be ultimately absorbed into the blood. Past studies have shown this could be as low as 1%. Scientists refer to this as poor bioavailability, a term for how much of an ingested drug is available to the body to use.

Srivastava's prototype looks, behaves and performs like a capsule, he says. To maximise absorption, it is designed to release insulin only in the presence of what he calls "activation switches". The acids, enzymes, and microbes of the GI tract are all potential stimuli, he says. The researchers are also fine-tuning an insulin formulation for the microdevice to deliver. Globally, self-organising microdevices are being tested for biomedical applications that require highly precise navigation and control, such as imaging and drug delivery. But they face many hurdles on the way to the clinic.

The prototype will undergo pre-clinical studies on animals. If it clears these, it will undergo human trials.

Nearly 24 crore Indians live with either diabetes or pre-diabetes, Srivastava observes, quoting statistics from a 2023 ICMR study. His goal is to bring a solution that capitalises on India's strengths in oral drug delivery, he says.

CAUSE CEREBRAL

Device maps brain injury in accident victims.

Shailesh Govind Ganpule teaches Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, but his work over the past 10-15 years has focused on brain injuries. An Associate Professor at IIT Roorkee, Ganpule has studied the impact of Improvised Explosive Device (IED) blasts and bullets on the brain. He has worked on, among other aspects, how bullets hit helmets and the kind of brain, spinal cord, or neck injury they cause. About five years ago, he decided to add a new dimension to his work by studying heavy impact trauma on the brain in accident victims, specifically those injured in two-wheeler accidents. This eventually led him to develop a small, coin-sized device – 28 mm in diameter and approximately 6 mm in thickness – that captures granular details of head movement in a 3D space, including linear accelerations and angular velocities experienced by the head, to detect the nature of brain injuries. It looks at a range of biomechanical parameters to assess the strain in the brain, identify the critical locations affected, and determine the severity of the injury. The device records data at 1 millisecond intervals and uses computer models to predict the severity of brain injury. It is also equipped to alert the emergency contacts of the accident victims.

SHAILESH GANPULE Shailesh Ganpule plans to test his device with human volunteers to generate head rotation and movement data.

The device can be worn using a headband or mounted directly onto a helmet. Ganpule has approached helmet manufacturers about this, but has yet to receive a positive response. He believes their lack of interest may stem from concerns that integrating the device would increase production costs.

The scientist’s work on heavy impact trauma on the brain in accident victims led him to develop a coin-sized device.

Ganpule's device was at technology readiness level (TRL) 3 when he first learned about the FIW grants. He felt that the grant would help make the device a real-world product and bring it to TRL levels 5-6. Since the grant began in May 2025, he has been testing the device in real-world scenarios. He plans to use full-body dummy models to recreate real-world crash scenarios and test the device's robustness in generating signals. Going forward, he also plans to test the device with human volunteers to generate actual head rotation and movement data.

Ganpule is also developing a computer model that uses biomechanical data from the device to predict the type of injury, the specific areas impacted, and the possible clinical management strategy. To do this, he is collaborating with clinical researchers at the Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital and the Institute of Nuclear Medicine & Allied Sciences in New Delhi. "They have a lot of data on the blunt impact patients, but the mechanical history is not known," he says. Ganpule wants to use this clinical data to train the computer model. The hospitals will provide anonymised case descriptions without revealing the clinical outcomes. Ganpule and his colleagues will then run the simulations and generate predictions using the computer model. Once this is complete, they will compare the predicted outcomes with actual clinical findings. "This will be a real litmus test for our model," he says. This approach will eventually help the computer model become increasingly accurate and reliable at predicting injury patterns based on biomechanical data collected by the device.

RAY OF HOPE

Using diagnostic X-rays for therapy.

At his laboratory in IIT Hyderabad, Aravind Rengan explores the wide-ranging uses of nanomaterials. One of them is how nanomaterials can impact cancer therapy. He is developing nanomaterials that act as radiosensitisers: molecules that selectively accumulate in cancer cells, making them more responsive to radiation therapy and potentially reducing the X-ray dosage required.

Cancer radiotherapy involves using high doses of X-ray radiation to either kill the cancer cells or damage their DNA enough so that they cannot grow. Typically, these therapies require 20-80 grays of radiation over time. Only specialised radiotherapy centres that require trained human resources and are expensive to establish can provide these therapies. Advanced treatment modalities, such as proton beam therapy, cost even more. It is therefore no surprise that India's radiotherapy requirements are not fully met. A 2025 study in BMC Cancer (bit.ly/Cancer-Radiation) notes that 58% of all cancer cases in India require radiotherapy treatment, but only 28.5% can access it.

To meet this shortfall, Rengan has an ambitious idea: use diagnostic X-rays for radiotherapy. "If we can convert all the diagnostic centres into therapeutic centres, then we don't have to worry about setting up radiotherapy centres," Rengan says. This is because setting up a radiotherapy centre is costly. Diagnostic X-ray machines, on the other hand, cost less, and there are already several diagnostic centres across the country, he says. Nanomaterials are his ally in this quest.

The intensity of diagnostic X-rays is typically one-thousandth to one-hundredth of that of radiotherapy. A lower dosage is less damaging and is better for imaging, but not strong enough to kill cancer cells. To enable low-dose diagnostic X-rays to kill cancer cells, Rengan wants to use specially designed nanomolecules that can radiosensitise cancer cells — making them absorb more radiation even with low-dose X-rays.

In collaboration with other researchers in chemistry, he is currently developing these nanomaterials "We are now working with gold, ruthenium, silver, and many other materials. These are molecules where they have atoms of inorganic material bound to other groups," he says. Some of the nanomaterials he is developing behave like cisplatin, a platinum-based chemotherapy agent that has been in therapeutic use for a long time. It has good radiosensitising abilities as well. Referring to cisplatin, Rengan says that there are chemotherapy drugs on the market that also act as radiosensitisers. While this is not entirely new, the existing drugs cannot "drastically" reduce the dosage. "Instead of, say, where you use 10 grays, you may reduce it… to maybe 5-6 grays, but it is not going to go to that level of ultra-low dose," he says. With the nanomaterials that Rengan and his colleagues are preparing in the lab, the required dosage can be 1,000 times lower than the current radiotherapy dose." These nanomaterials are working like a chemotherapy agent and also acting as a very good radiosensitiser," he explains.

Currently selected for level 1 of the ICMR FIW grant, Rengan and his colleagues are working to generate preliminary data and then apply for level 2 of the grant.

GREEN SIGNAL FOR RED

A rapid four-in-one test seeks to make blood donations safer.

Amita Gupta is an old hand at developing rapid diagnostic tests. Back in 2001, she was part of a team of researchers that developed NEVA HIV, a rapid HIV diagnosis kit that was later acquired by Cadila Pharmaceuticals. Gupta always felt that the basic technology developed for NEVA HIV could be translated into tests for other diseases. "It's like a platform technology that can be adapted for any infection," says Gupta, Professor and Head of the Department of Biochemistry, the University of Delhi South Campus.

When Gupta first found out about the FIW grant, she knew it was time to develop another blood-based test. Not just for HIV this time, but a set of four diseases — HIV, hepatitis C, hepatitis B and syphilis — that every bag of donated blood must be tested for.

The current standard practice is to collect blood at donation camps and transport it to labs for processing. After that, it is tested and discarded if found to be infected with any of the diseases. Only uninfected blood is stored and used for transfusion purposes. Although this is the standard practice nearly everywhere in the world, Gupta identifies several problems with this methodology. In this process, blood is processed by lab workers before being tested for infection. This means that, from the donation site to the lab, there is a chain of processing, and at each step, there is a risk of exposure to contaminated blood. "This is a biohazard," she says.

Gupta feels that blood should be tested before donation, rather than unnecessarily taking blood from a person who is not fit to donate it or is currently carrying an infection. Additionally, it will minimise the disease exposure risk for healthcare workers and lab technicians, and the risk of contamination from blood bank leaks. "We want to develop a test that could be done on site, prior to the collection of blood, so that this entire process and supply chain would be free of risk and hazard," she says.

Since receiving the FIW challenge grant, Gupta and her colleagues have been developing reagents that will enable testing for the four blood-based infections in minutes. For each of the four diseases, separate testing reagents have to be developed and then validated for performance, specificity and sensitivity of detection. After individual reagents demonstrate acceptable performance, the researchers will prepare a cocktail of reagents to enable a single test for all four diseases. Tie-ups for initial testing of reagents for each disease are already in place with blood banks. However, once the reagents are ready and validated at a small scale, larger evaluations will be done, and eventually, industry partnerships will be required to take it forward. ICMR's support in running multicentric trials across the country would be crucial, but that is at least a couple of years away. "We are looking at a two-to-three-year timeline to have the cocktail ready," she says.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH